You didn’t want your lowlife cousin to come to the party, but he came uninvited with your sister. Dog breeding can be like that. Some relatives can’t be avoided. Genotype, the genetic makeup of a dog, involves the extended family.

My mentors taught me that linebreeding, the practice of breeding dogs who are somewhat related to one another, was essential to setting type and solidifying positive characteristics in a breeding program. Outcrossing, or breeding unrelated dogs, is necessary periodically to maintain vigor and vitality, and should be done based on phenotype—the physical appearance of the dog.

Successful and responsible linebreeding requires an intimate knowledge of the dogs in the pedigree and a working knowledge of their littermates and progeny. Strengths can be magnified, but so can health or temperament problems, which may crop up like the uninvited distant cousin. Learn as much as you can about dogs on the pedigree grid, but learn also about their littermates. The qualities found in a black-sheep uncle or wanton niece could bring an unwelcome surprise in your next litter if you’re not vigilant.

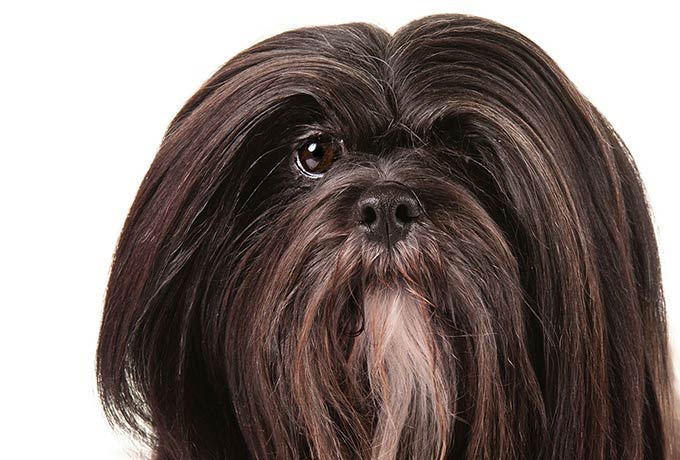

Outstanding relatives are the key to understanding why an otherwise average dog could be a preeminent producer. In the Lhasa Apso breed, the late Sinbad of Abbotsford, ROM, is one such dog. (Abbotsford Lhasa Apsos) were at a crossroads in their pioneer breeding program and did a “move forward or perish” breeding. Sinbad was the only male in the litter, and “only could have gone to a dog show in a wheelbarrow,” according to Mrs. Roberts. He had a long muzzle and was largish and a bit of a clunk. He was healthy, sound, and had the wonderful temperament that characterized the line, and produced puppies that reflected his heritage, not himself. He sired at least 14 AKC champions, including group and Best in Show winners. Some 40 years later, occasionally, down from him will appear a long-muzzled dog who is a wonderful producer.

The late (Chen Lhasa Apsos) strongly favored breeding uncle-niece or aunt-nephew to scour the gene pool, doubling strengths and pulling out qualities one might not otherwise know are lurking. This practice gives the breeder an advantage in planning future litters. One of my most cherished possessions is an annotated, handwritten pedigree done by Pat of one of her first Lhasas, which goes back to the original imports. Her notes impart a wealth of information about the physical characteristics of many early dogs that would not be otherwise known.

Outcrossing—breeding dogs who are apparently unrelated—is important to maintaining strength. An infusion of new genetic material bolsters fertility and physical vitality and can bring in needed improvements in structure, health, and temperament. However, in a breed with limited antecedents, paper does not tell the entire story. A pedigree with no common ancestors in four generations can still have a strong inbreeding coefficient based on DNA. This is relatively new knowledge and potentially explains why outcrossing Lhasa Apsos, within the United States, at least, can yield surprises. This concepts merits study and consideration. It also makes a case for the value of the Gompa landrace colony discussed in a previous column, which now are AKC registered. There is at least one champion credited to a Gompa sire.

Breeders have tools to build a meritorious line that improves the breed. One of the most important is to know the family history of the dogs we are breeding.

—, ; June 2015 AKC Gazette